Shadow impact is a common concern for residential development. Most DAs will be accompanied by:

at least one type of ‘shadow diagram,’ and

an assessment within the statement of environmental effects (‘SEE’) of the shadow impact and whether this complies with the relevant planning controls.

Overshadowing controls are usually found in a Development Control Plan, under headings of ‘shadow impact’, ‘overshadowing impact’ or ‘solar access.’

Overshadowing controls vary between local government areas but they are usually assessed with reference to the worst case situation, ie midwinter, and usually at 9am, noon and 3pm.

For larger residential flat buildings overshadowing controls are found in the NSW Government’s Apartment Design Guide Objective 3-B2 (you will also need to look at Section 4A).

Shadow diagrams

There are three main types of overshadowing diagrams;

Plan view;

Elevational; and

View from the Sun.

Ideally, each type of diagram will provide information for:

The shadow of existing structures;

The shadow of proposed structures; and

Shadow arising from any element that is non-complying, for example, non compliant building height.

Plan view shadow diagrams

Plan view diagrams show the shadows of new development as they fall on the ground. They are helpful in understanding whether your garden is going to be overshadowed, for example. They do not directly show how additional overshadowing will affect windows.

The diagram above is a very simple ‘Plan View’ shadow diagram for a proposed townhouse development at 21 Smith Street and a neighbouring existing dwelling house at no. 23 Smith Street.

The diagram shows:

No.23 will not be impacted at either 9am or 12 noon midwinter (red and blue shadow lines);

Over 50% of No.23’s rear garden will be impacted at 3pm (green line).

Note that the shadow plan does not show what shadow impact would occur on no.23’s western side elevation (B) or northern elevation (A). However, because the 3pm shadow line extends a long way along the northern side (A) this would be an indicator that windows on the west side of that northern elevation, as well as any windows on the western elevation (B), are likely to be impacted. In this circumstance it would be quite reasonable to raise shadow impact on these windows as a concern, and to ask that ‘elevational shadow diagrams’ be provided for both northern and western elevations.

For comparison, if the shadow from the proposed development only ‘grazed’ No 23’s western elevation along its full length (say, if no. 23 was located much further away from the common boundary) then (providing the windows were not at a lower level) impact on the windows of either elevation A or B would not occur. The shadow from no 23’s fence, for example, does not cause any overshadowing of the western wall.

Note that the shadow impact of trees and vegetation is generally not taken into account, except in situations where the density of vegetation is so dense and of sufficient ‘permanence’ that it would be unrealistic to disregard it -see the link to the Court’s planning principle on shadow assessment below.

Plan view diagrams become increasingly difficult to understand in highly built up areas and areas of steep/varied topography.

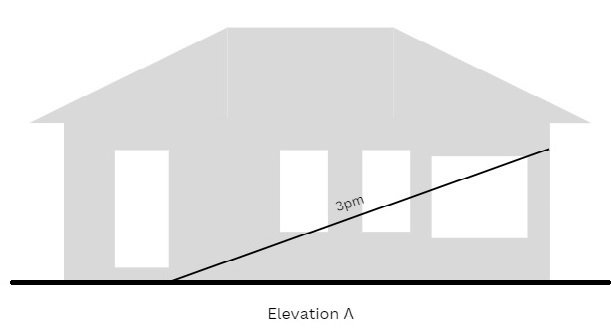

Elevational shadow diagrams

Elevation shadow diagrams show the shadow of a development projected on walls. If you are worried about shadow impact on windows and internal spaces, these are the diagrams you want to see.

The ‘elevation’ is the side, front or rear of your house that is impacted. As shown in a shadow diagram it should be based on survey information or measured drawings by the architect, so that it accurately depicts the location of openings, sill (bottom) and top heights of windows.

Note: You might need to see more than one elevation shadow diagram to understand the total impact. In the example given above for Plan view shadows, for example, you would need to see both the north (A) and west (B) elevation shadow diagrams.

‘View from the Sun’ diagrams

View from the sun diagrams rely on a 3D computer model being constructed which shows a proposed development in the context of existing surrounding buildings. Once this model is constructed a series of views are generated based on the height and position of the sun at various times of the day.

Essentially, the diagrams represent the sun ‘looking down at the proposed development’ and anything the sun cannot see (ie it is blocked by the proposed development) is something that is therefore in shadow at that time.

View from the sun diagrams are the simplest shadow diagrams to understand. They have the benefit of showing impact both on adjoining buildings as well as on surrounding ground levels.

Their only real disadvantage is that because the shadow is not projected ‘to scale’ it is not possible to determine, with precision, what percentage of a window or rear garden will be overshadowed.

View from the Sun Diagram prepared by Innovate Architects

The above ‘View from the Sun’ diagram presents good detail both of the proposed development (marked by a red star) and the existing surrounding buildings. It shows how balconies on the existing building to the south are overshadowed at 2pm but gain increasing solar access as the sun’s position moves round towards 3pm.

How shadow impact is assessed

The starting point for any assessment of shadow impact is the relevant control, found in the Development Control Plan or (for larger residential flat buildings) the Apartment Design Guide. Overlain on this, however, are concepts of practicality and reasonableness, into which a number of factors can come into play.

If a site currently developed with a cottage but zoned for three storey residential flat development is directly north and uphill of a neighbouring site it will, for example, be very difficult to avoid significant solar impact, at least not without effectively sterilizing the site’s development potential. In this circumstance the assessment will seek a balance between the intent of the development site’s zoning (to enable new, higher density development) and the competing objective of the overshadowing control, (to protect amenity). The assessment officer is likely to look at skilful design which optimises the solar access by lowering parts of the proposed building, increasing setbacks and so on, but if site circumstances make retention of solar access impractical, a variation to the planning controls is likely to occur.

Further useful guidance on how shadowing impact is assessed can be found in the NSW Land and Environment Court’s Planning Principles (para. 133 onwards).